Follow the brown signs

The bell doth toll for the Bromley Museum

Last week those of us who’d been watching the increasingly downward spiral of events unfolding at a small local museum in south east London finally heard the news confirmed that no one wanted to hear. It was not at all unexpected but nevertheless still immensely sad and frustrating that the local authority eventually announced they would be closing Bromley Museum forever as of the 1st of October 2015. No plans have been put in place to rehouse and show the collection elsewhere (unless you call a few display cabinets in an unstaffed corner of a local library a new “museum”), so after 50 years of celebrating Bromley’s history and heritage through the medium of 6,000 objects and countless varied exhibitions there is soon to be next to nothing left, some of the collection will be put in storage and a fair amount sold off. The final nail in the coffin followed a long string of gossip, meetings, ill-thought-out emails from on high and “consultations” that I’m sure precede any such local authority museum closure (of which there have been many, as evidenced by The Museums Association in 2012) but when I heard with finality that the largest (and also one of the richest) London boroughs, with such a huge and multifaceted history would soon have no museum at all, instead of feeling enraged and bitter towards the decision makers all I felt was a sense of total and utter inevitability. A prolific blogger and championer of all things museum, Tincture of Museums, volunteered at the museum (and others in London) and wrote a heartfelt blog about the announcement which will give you more on the details here.

Last week those of us who’d been watching the increasingly downward spiral of events unfolding at a small local museum in south east London finally heard the news confirmed that no one wanted to hear. It was not at all unexpected but nevertheless still immensely sad and frustrating that the local authority eventually announced they would be closing Bromley Museum forever as of the 1st of October 2015. No plans have been put in place to rehouse and show the collection elsewhere (unless you call a few display cabinets in an unstaffed corner of a local library a new “museum”), so after 50 years of celebrating Bromley’s history and heritage through the medium of 6,000 objects and countless varied exhibitions there is soon to be next to nothing left, some of the collection will be put in storage and a fair amount sold off. The final nail in the coffin followed a long string of gossip, meetings, ill-thought-out emails from on high and “consultations” that I’m sure precede any such local authority museum closure (of which there have been many, as evidenced by The Museums Association in 2012) but when I heard with finality that the largest (and also one of the richest) London boroughs, with such a huge and multifaceted history would soon have no museum at all, instead of feeling enraged and bitter towards the decision makers all I felt was a sense of total and utter inevitability. A prolific blogger and championer of all things museum, Tincture of Museums, volunteered at the museum (and others in London) and wrote a heartfelt blog about the announcement which will give you more on the details here.

Bromley is my hometown, I’ve lived in and around South East London most of my life and the museum is in the memory of most of us who grew up there, either through the obligatory school trips or visit with the family. It is true that the museum had its issues, it isn’t in the most accessible location hidden away down a side street at the arse-end of Orpington High Street in the furthest flung area of the borough where London meets Kent. There were of course justifications made for it’s closure; dwindling visitor numbers, the great cost of maintaining the 13th century building in which it is housed and the inaccessibility of the place in general (which closing for lunch everyday and at weekends hardly helped!). However what makes me sad is not that these issues were brought out into the open, they are familiar issues shared by a hefty whack of the heritage sector in general at the moment, but it is the fact that there is such apathy and general lack of motivation from anyone with any clout to face those issues head-on and, shock horror, maybe even spearhead a reinvention of the museum and turn it around (ironically just down the road in Beckenham stands the Bethlam Museum of The Mind which over the past few years stands out as a spectacular example of achieving exactly that). To add insult to injury the museum had made a successful bid to the Heritage Lottery Fund in 2011 which would have eventually enabled the old building to be restored and made more accessible, to extend the exhibition space and put in more engaging programmes, but after a huge amount of work from the team at the next stage of the process (which was looking very promising) the council started dragging its feet, then finally it emerged the bid had fallen through due to Bromley’s failure to commit funding to the museum for the next 25 years. After kindling the fire with hope and enthusiasm the first fat droplets of apathetic rain began to fall. Clearly the council had no desire to continue funding the museum even after there was potential for huge investment from another organisations coffers. Instead it was far easier to face a short term backlash of public outcry and a bit of bad press and quietly close the place, then heave a huge sigh of relief that the museum would be no longer one of the millstones hanging around the poor council’s neck. Add that to reaping the benefits of selling off the oldest building in the borough and the surrounding land and who’s surprised by Bromley council’s decision? But I’m not writing this piece to cast blame or to air frustrations, I’m far more interested in trying to get my head around why and how these decisions continue to be made and what, if anything, we can do to appeal to and change the minds of the decision makers who literally need an education in the great value of maintaining museums like Bromley.

It surely goes without saying that connecting kids with where they live, providing them with learning opportunities to give the places around them meaning and encouraging them to be proud of their home town instils a sense of belonging, pride and community when they grow up, that must be good for their connection to the world in general but also for their own self esteem and well-being (there are more and more studies thankfully being published that provide evidence for this idea coming from leading acedemic institutions and bodies such as the Museums Association, who have case studies on their website, see also their important Museums Change Lives policy document which indicates how). In addition local museums offer something unique; for kids they are a place to view and interact with a varied collection just down the road and offers an alternative to the traditional classroom learning, and for us adults (even those who aren’t museum geeks like me) we suddenly find our interest peaked by unfamiliar stories about all too familiar places we may never have given a second thought before. Local museums show us new things about the fabric of the lives we live, they tell us unique stories about the places we inhabit, the very places we too define. Local museums tell us stories about ourselves. The role museums can play in improving both physical and mental well-being is now far more widely accepted and are the buzz words on many a heritage professionals lips at the moment. This is encouraging because finally evidence based theory and practice is starting to get noticed by the decision makers. The focus on preventative healthcare and channelling more money into a less traditional medical side of NHS treatment seems to be making a slow but important difference and the economic impact that arts and heritage engagement have are also being brought to the fore (the Arts Council published an important paper in March this year outlining the research and data to indicate how valuable museums really are the economy, it is here).

But while having stats and data to back up what we who love arts, culture and museums already know can obviously be used to help decision makers understand how important engagement is, I also think we must not to lose sight of the romance and unpindownable nature of what we humans get out of engaging with these places. And this is a plea not just to those holding the purse strings but also to those we are aiming to engage, those who may not see the value in what is being offered at museums and thus simply go to make up the statistics of the dwindling audiences which those on high point at as evidence that museums don’t deserve their support. The great joy of human beings is our unique perception of the world around us, we don’t all feel the same nor notice the same things, each one of us sees the world differently and we have our buttons pressed by different stimuli. This is why I feel it’s so important to value and support public access to the many varied and imaginative organisations such as museums and arts centres that help knit together the fabric of a healthy society.

I remember being genuinely delighted when I discovered David Bowie had grown up just down the road from where I lived and had walked the same streets that I did. To be honest I didn’t have much interest in David Bowie until then, but finding out more about him at Bromley Museum (with added geeky research at home) I was genuinely inspired by the boy from the suburbs who never fitted in, struggled with his overwhelming desire to create in a world that didn’t nurture his spirit, eventually overcoming his private struggle to finally rise to international musical stardom. “You too could achieve something phenomenal Amanda, even if you are only from bloody Bromley” I told myself quietly.

Years later I frequently referred to David Bowie as an inspiration during my campaign to transform a decaying old Victorian coaching inn on Bromley High Street into an arts and community centre (I also emailed him a few times but I think he’s quite busy…). The project was fraught with difficulties from the outset, the building was in a terribly dilapidated state, costs to renovate and restore would be in the millions and the lease situation was a huge tangled knot of pub company (read: property investment company) profit maximising bureaucracy. I always knew it wouldn’t be easy but I also knew there were passionate people who would get behind me and there was money out here to be accessed for projects exactly like this one. I also knew how much of a dearth there was of creative arts in the town. In my opinion every town needs a physical place to go to and free one’s creative spirit, somewhere that’s open all day and offers a varied range of activities to appeal to everyone. For such a big town I was incredulous at the lack of a vibrant arts and community hub that exist pretty much in every other borough around, and knew I wanted to do something about it. Incidentally David Bowie had felt exactly the same about our suburb in the late 1960s when he began hosting a weekly Arts Lab on Sunday nights at the Three Tuns pub (now a Zizzi’s) in Beckenham. He was passionate about the place and his words in an interview with Melody maker in 1969 made me want to weep in solidarity, he said: “I run an arts lab which is my chief occupation. It’s in Beckenham and I think it’s the best in the country. There isn’t one pseud involved. All the people are real – like labourers or bank clerks. It started out as a folk club, arts labs generally have such a bad reputation as pseud places but there’s a lot of talent in the green belt and there is a load of tripe in Drury Lane. I think the arts lab movement is extremely important and should take over from the youth club concept as a social service. We’ve got a few greasers who come and a few skinheads who are just as enthusiastic. We started our lab a few months ago with poets and artists who just came along. It’s got bigger and bigger and now we have our own light show and sculptures, et cetera. And I never knew there were so many sitar players in Beckenham.” Bowie’s words made me even more convinced that this venture would be successful in Bromley, but unsurprisingly from those at the top there was little interest. Tincture of Museums has outlined many of the prevailing attitudes held by those decision makers at Bromley Council, and I experienced them myself at meetings I had to virtually beg councillors to attend. When the leader of the council attended one such meeting (the first and only one I may add) he arrived late and sat directly behind our Chairman who was giving a presentation. One councillor, the Portfolio Holder for Renewal and Recreation once asked me why I was bothering with the such a complex project, “it would be far cheaper to simply knock the place down, except that’s not possible because it’s listed…” Facing down the apathy at the council was almost worse than the profit hungry capitalists at the pub company. When we presented our ideas and the potential for the project (which was being given strong support from various funders like HLF and the Social Investment Business) the silence was deafening. I fear we would have got the same reception if we had walked naked into the council chamber with placards declaring the end of the world was nigh. The total lack of imagination and narrow focus on the things that only made money (and quickly) was their overriding priority (“would we consider putting a Jamie’s in there?”), so forget your community engagement and artistic endeavours because they have no place in this town (NOTE: I just reread this paragraph and realised it sounds terribly negative about everyone at the council. Of course there were officers and councillors I came across who were supportive of our work, many of them probably as frustrated at the council workings as we were, although they never said it. One who stands out was Peter Fortune, who clearly genuinely cares and takes a more energetic approach to serving the residents of his ward, which used to be the Crays. It would be wrong of me not to thank him here for time spent with me when things all felt too impossible but his encouragement and belief in the need for an arts centre for the people of Bromley always kept me going).

It cannot be denied that there is a dismal lack of arts provision in Bromley, it is simply not something seen as beneficial for the town by those in charge, probably because they associate arts with little or low profits, and this is detailed in a report published by the council back in January. The vast bulk of arts funding, £316k p/a, has long been allocated to the private company Ambassador Theatre Group who currently run the council owned Churchill Theatre. In return for such funding the theatre apparently uses £50k to run outreach projects and work with amateur dramatics groups, the rest simply goes to lessening the heavy losses that the theatre group are experiencing at the moment. Other projects that are referred to are the Bromley Youth Orchestra and the social enterprise set up by the council when they decided they no longer wanted responsibility of running their leisure services. But that’s not exactly arts provision guys… The report sites a lot of external funding that had been won for the delivery of these projects and collaborations with other charities and not for profit ventures (that often rely on voluntary workers) but nevertheless they were happy to list them as part of their own arts provision programme. The report only goes to make it clearer how likely Bromley is to become even more of a cultural wasteland. It seems bizarre to me that there can still be such a lack of insight into the great value of arts and cultural engagement when there is so much evidence out there to show it. Fortunately, although it may take some time, the Government have started a new initiative that has begun to restore my faith called (don’t laugh) What Works, which centres around drawing on the great bodies of research going on in our most learned institutions that can be formally gathered together and used to actually make policy decisions on proven facts (I know, revolutionary right?).

While undertaking my extensive research on all things brown sign related over the past 6 years I have been more and more aware of this increasingly apparent move away from the idea that learning, inspiration and engagement are valuable and important concepts in their own right, and that they should naturally be encouraged simply for their own sake’s, they apparently now need constant justification for their existence.

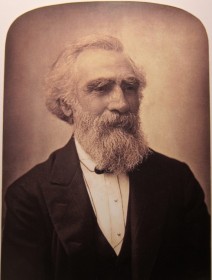

I’m always drawn to Victorian philanthropists such as John Passmore Edwards (funder of one of my favourite libraries of all time in East Dulwich), who dedicated his whole life to providing the means for every person regardless of age, race, religion, creed or colour to access resources not only for their own individual pleasure but also for the benefit of the whole of society. Passmore Edwards funded no less than 70 public buildings and institutions, many of which still serve their original purpose today. He wrote in his autobiography: “When I was a boy I should have jumped with joy if I could have found a corner in a reading-room for an hour or two a day, or have been enabled to take books home as boys and girls can do now where public libraries exist. A majority of people cannot say, with Prospero in the Tempest “My library was dukedom large enough.” They might, however, and ought to, be able to participate in the advantages of a library created and maintained by public action”. From their conception the obvious need and value to society of these institutions has been clear to a small number of forward thinking people not driven by profit, and more often than not it has been down to them alone to tirelessly campaign for or even fund these ventures themselves. But what worries me is what happens when their legacy is not continued generations or maybe even only a generation later? Such fresh and uplifting places that were once so inspiring and enlivening are changed beyond all measure when they are put into the hands of people who simply do not share the fundamental original convictions. It makes me sad that any museum facing closure started out with such optimistic aims, yet years down the line the baton has obviously not been passed to those with the expertise or motivation to keep running with it, as was clearly the case with Bromley Museum. In this increasingly business focussed and profit driven world the notion people should be inspired, to enjoy for enjoyment’s sake and spend time connecting with the world and society through visits to museums scores very low on the obvious profit/loss calculator, the costs have been calculated yet there is absolutely no understanding of their value. Inevitably investment in these “fluffy” non-profit making areas are the first to be pulled when money gets tight, but the ironic and fabulous thing about museums, libraries and other such public institutions is that they were never designed to make money nor be in any way run as highly profit making ventures. The cabinets of curiosities that precede the modern museum as we know it today were all about the sharing of knowledge, enlightening people of things they knew little about and showing off novel things. These places simply existed to make people think, question and wonder about the world around them, their success was measured on that alone, not on average sales in the gift shop.

I’m always drawn to Victorian philanthropists such as John Passmore Edwards (funder of one of my favourite libraries of all time in East Dulwich), who dedicated his whole life to providing the means for every person regardless of age, race, religion, creed or colour to access resources not only for their own individual pleasure but also for the benefit of the whole of society. Passmore Edwards funded no less than 70 public buildings and institutions, many of which still serve their original purpose today. He wrote in his autobiography: “When I was a boy I should have jumped with joy if I could have found a corner in a reading-room for an hour or two a day, or have been enabled to take books home as boys and girls can do now where public libraries exist. A majority of people cannot say, with Prospero in the Tempest “My library was dukedom large enough.” They might, however, and ought to, be able to participate in the advantages of a library created and maintained by public action”. From their conception the obvious need and value to society of these institutions has been clear to a small number of forward thinking people not driven by profit, and more often than not it has been down to them alone to tirelessly campaign for or even fund these ventures themselves. But what worries me is what happens when their legacy is not continued generations or maybe even only a generation later? Such fresh and uplifting places that were once so inspiring and enlivening are changed beyond all measure when they are put into the hands of people who simply do not share the fundamental original convictions. It makes me sad that any museum facing closure started out with such optimistic aims, yet years down the line the baton has obviously not been passed to those with the expertise or motivation to keep running with it, as was clearly the case with Bromley Museum. In this increasingly business focussed and profit driven world the notion people should be inspired, to enjoy for enjoyment’s sake and spend time connecting with the world and society through visits to museums scores very low on the obvious profit/loss calculator, the costs have been calculated yet there is absolutely no understanding of their value. Inevitably investment in these “fluffy” non-profit making areas are the first to be pulled when money gets tight, but the ironic and fabulous thing about museums, libraries and other such public institutions is that they were never designed to make money nor be in any way run as highly profit making ventures. The cabinets of curiosities that precede the modern museum as we know it today were all about the sharing of knowledge, enlightening people of things they knew little about and showing off novel things. These places simply existed to make people think, question and wonder about the world around them, their success was measured on that alone, not on average sales in the gift shop.

Along similar lines, in 2013 Croydon Council (our neighbouring London borough) announced they would be selling off some of the multi-million pound collection of Chinese ceramics from their museum collection to help fund a revamp to the 1960s brutalist edifice the Fairfield Halls. Not only was this a travesty for the museum, its collection and the people who would no longer be able to see it but it was also actively flouting the terms of the bequeathed collection. Raymond Riesco, a Croydon businessman had an agreement with Croydon Council that they would buy part of his estate on his death, putting his collection “in trust for the people of Croydon”. There was much debate about the ethics of the decision and the Museums Association permanently banned them from ever applying for any museum accreditation ever again after the sale went ahead. There were over 650 acquired pieces in the original collection back in the late 1950s but it was discovered through a freedom of information request that only 230 remained in the council’s possession. Two hundred and ninety two pieces were sold in 2 sales during the 1970s and 80s, incredibly 39 pieces were declared stolen at an unknown date or dates, leaving 89 objects simply missing and unaccounted for. Of the original collection then, most of which had already been sold/lost/stolen/broken, 22 pieces were offered up for auction in Hong Kong. The council admitted they had no idea where the unaccounted for pieces were because no records had been kept and the staff who worked at the museum during that time were no longer there. Literally millions of pounds worth of pieces were allowed to fall through the council’s hands and the care in which they had been entrusted equated to that of a group of 5 year olds. It is absolutely shocking to me that such bequests and gifts that make up these collections, that are made under very specific terms by people who have poured so much of their effort, money, love and time into them specifically offer them up to institutions they think they can trust so they can be freely available for the public to view and enjoy. Yet how is it then possible that these terms can be so easily ignored if so suits a council one day? The ultimate irony is that the collection made only half their estimated figure, with only 17 of the 22 pieces being sold on the day, leaving the council around £8m short for the refurbishment of the Fairfield Falls anyway.

So what is to be done? Well in my opinion at least one problem we face is the way our government and local councils are set up. A disproportionately small number of people decide what will happen in our ever growing communities. Whether they base their decisions on any evidence or statistics, whether they are open to listening to the public (if hearing our opinions would make a difference anyway) and whether they are swayed by other motivations such as personal gain or wielding authority is totally irrelevant, the power is firmly in their hands and once those decisions are made there is virtually no way to revoke them. During my Bromley Arts and Community Initiative campaign I thought long and hard about the issues I and many other community groups and charities faced with the council and I decided instead of bemoaning the issues that I would make myself part of the solution, and so I would stand as an independent councillor for Bromley. I wanted to dilute the stagnant pond and breath some fresh thinking and new life into the staid and apathetic ways of the council, show them that there is another way to get things done and not to be scared of taking an imaginative approach. Even small amounts of public investment given to the right people can turn into something unfathomably successful, mainly because the right people are driving it. One day I made a speech to a large meeting of representatives from all over Bromley’s third sector about our project and afterwards a lady from an older people’s charity who had been voluntarily working tirelessly for over 25 years approached me. She was excited by the idea of the pub becoming an arts centre and the prospect of having outreach sessions for those who might not be able to physically get to the centre. I told her I was considering standing as an independent councillor and I’ll never forget what she said: “don’t do it Amanda, it’ll suck the last drop of life out of you. Your fight, determination and aspirations will drain away, it’ll be the worst decision you ever make I promise you”. I tried to reassure her that I wouldn’t be running because I thought it would be easy or fun, but that if people like me who believed so passionately that they could make a positive difference to their communities didn’t get into the decision makers private echelons then how really would we ever make any difference at all. She agreed with me, she knew it was true but she had also shown me the cost at which it might come. I was passionate about changing Bromley for the better but when I would be a tiny minority in a depressingly fragmented and rigid institution, consistently seeing from the inside all the things that already made me so frustrated from the outside, how on earth would I be expected to hold onto my sanity? In his book How to be a Social Entrepreneur, Make Money and Change the World, Robert Ashton sums up this exact issue. The kind of people social entrepreneurs and campaigners are do not gravitate towards public office. They think out of the box, they test boundaries, they have unbudging belief in what they do, they are imaginative and they make things happen against the odds. Local councils and governments on the other hand are risk averse, those working inside them are part of a complex, unwieldy machine and no social entrepreneur would ever flourish bound by such shackles, but frustratingly these are the very people we need to be in on the decision making process.

In my opinion the system is broken and thus appealing to the likes of the councillors at Bromley Council is a complete waste of time when trying to illustrate the negative impact of closing Bromley Museum for good or highlighting the benefits of having an arts and community centre in the town, it will make no difference to their thinking, public funds will not be allocated to such ventures. Frankly until the system changes (vive la révolution?) those people who have absolute dedication to their cause and who make things happen for their communities in imaginative, creative, perhaps unconventional ways (probably inspired by someone they read about in a library book or learnt about at a museum) will continue to be underfunded and underutilised and the things that they fight for, like simply being human, will sadly continue to play second fiddle in the prioritisation of public funding stakes.